Microplastics in water resources are an emerging global concern because of their persistence, mobility, and potential ecological and human health risks. India’s rivers, lakes, aquifers, and coasts are increasingly burdened by microplastics. Over the past decade, evidence from field surveys and laboratory analyses has confirmed that microplastics (MPs) are now present across the country’s freshwater and marine systems, with hotspots near dense populations and industrial hubs.

What are Microplastics?

Microplastics are plastic particles smaller than 5 mm. They can be:

• Primary microplastics – manufactured small particles (e.g., cosmetic microbeads, industrial pellets, synthetic fibers).

• Secondary microplastics – fragments formed by degradation (photolysis, chemical process and physical abrasion) of larger plastic items such as bottles, bags, and fishing nets.

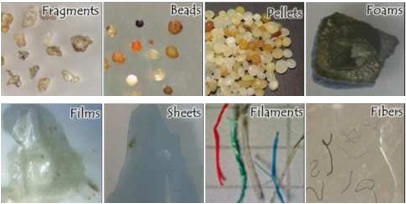

Shapes and chemical structures of Microplastics

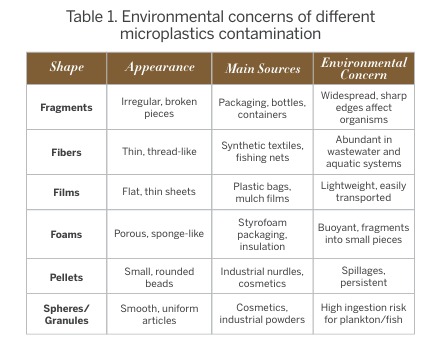

Microplastics in the environment occur in a variety of shapes depending on their source and degradation process. These shapes are important because they influence how particles move, persist, and interact with organisms. Across Indian studies, fibers and fragments are most common, typically <1 mm. Common Microplastic Shapes are:

1. Fragments

• Irregular, jagged pieces from the breakdown of larger plastic items.

• Common sources: bottles, packaging, bags, fishing gear.

• Often found in soils, rivers, and marine sediments.

2. Fibers (or Filaments)

• Thin, elongated strands resembling hair or threads.

• Sources: synthetic textiles (polyester, nylon, acrylic), ropes,

• nets, carpets.

• Major contributors: laundry e uents, fishing activities.

3. Films

• Thin, flat, sheet-like particles.

• Sources: agricultural mulch films, plastic bags, packaging films.

• Easily transported by wind and water due to light weight.

4. Foams

• Porous, sponge-like structures.

• Sources: polystyrene foam (Styrofoam), insulation materials, food packaging.

• Break down into very light particles that spread widely.

5. Pellets (Nurdles or Beads)

• Round or oval particles, either industrial feedstock pellets or microbeads from cosmetics/personal care products.

• Industrial spills and transport losses are major sources.

6. Spheres / Granules

• Smooth, uniform particles (smaller than pellets).

• Sources: scrubbers, resin powders, some fertilizers or coatings

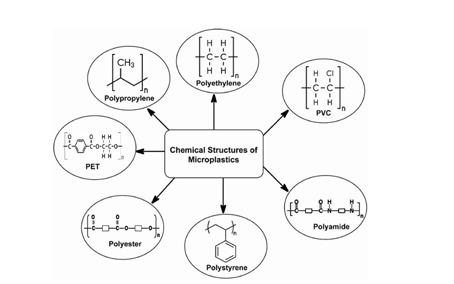

The most common microplastic polymer types in the aquatic environment are polyethylene (PE), polyethylene terephthalate (PET), polyamide (PA), polypropylene (PP), polystyrene (PS), polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), and polyvinyl chloride (PVC). Among these polymers, PE and PP are semi-crystalline polymers and PVC, PS, and PET are amorphous polymers. The mechanical properties of polymers are directly influenced by the degree of crystallinity. Figure 2 shows the chemical structures of some common MP polymers.

The other 17 MP polymers in urban wastewater includes acrylate, biopolymer, high-density polyethylene (HDPE), low-density polyethylene (LDPE), melamine, PP, PS, polyurethane (PUR), PVA, rubber, Teflon, and some unidentified polymers.

Microplastic studies in India by Researchers

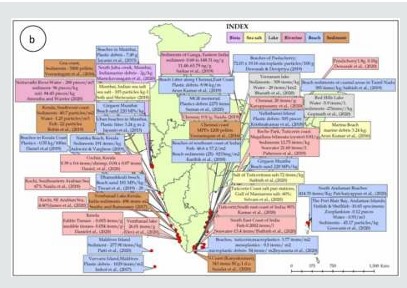

The studies done on microplastics are still in the nascent stage. The spatial distribution of microplastics in the di erent aquatic environments in India is shown in Fig. 3.

Rivers and lakes

There are quantifiable MP loads in a number of Indian rivers, particularly those that flow through urbanized catchments.

According to research on freshwater resources, concentrations in the Ganga, Adyar, and Kosasthalaiyar range from a few hundred particles per cubic meter, with polyethylene (PE), polypropylene (PP), and polyethylene terephthalate (PET) being the most common polymer forms. Land use, wastewater inputs, and storm-driven runo are all reflected in spatial variability. Microplastics have frequently been found in the water and sediment of Vembanad Lake (Kerala), the largest Ramsar site in India. Previous research found PE to be common, and more recent studies have described MPs in bottom and subsurface waters, highlighting continuous inputs and re-suspension. New site-specific research from other urban lakes (such Tamil Nadu) adds to the image of localized pollution caused by storm drains, road dust, and coastal activities.

Groundwater

While studies are still in their infancy, initial data suggests that urban groundwater may also be impacted. According to a recent study from Kozhikode, Kerala, MPs were found in most of the open wells that were investigated. PP and HDPE were prevalent, which is probably due to inputs from surface litter, leaky sanitation, and percolation through porous soils. This draws attention to a novel exposure pathway where intensive human activity meets shallow aquifers.

Coasts and estuaries

Microplastics have been found in beach sands, biota, and nearshore seas along India’s 7,500 km coastline. While more comprehensive syntheses highlight the Ganga– Brahmaputra–Meghna system’s significant plastic input to the Bay of Bengal, national monitoring, spearheaded by the Ministry of Earth Sciences’ National Centre for Coastal Research (NCCR), has carried out multi-year field studies on both coasts.

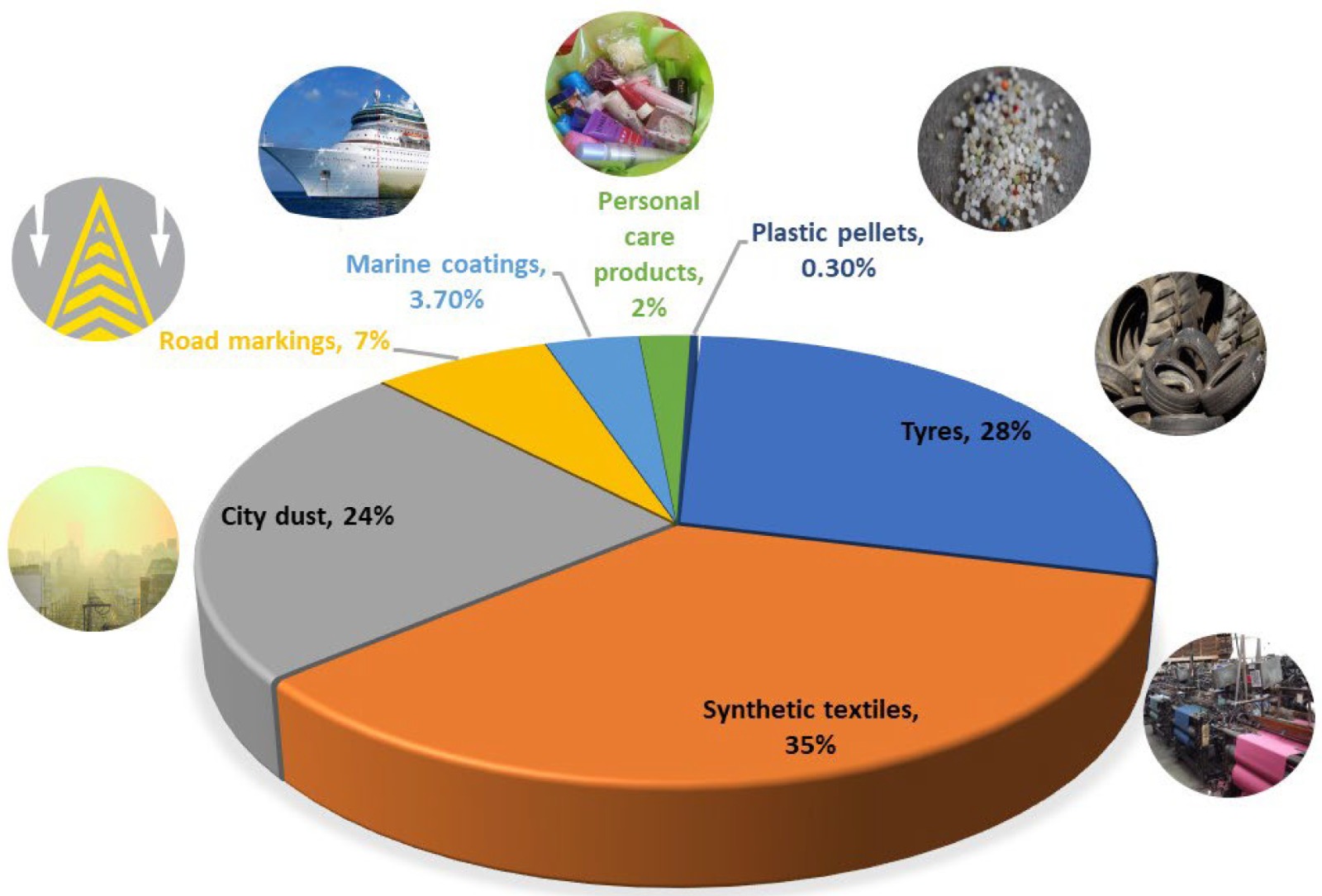

Sources and pathways

1. Municipal wastewater and stormwater

A portion of MPs are captured by wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs), but they also serve as transfer points, particularly for fibres and tiny pieces that evade traditional treatment. MPs in influent and partial removal across methods were recorded in a study on Ganga-basin sewage plants, highlighting sludge and effluent as important routes back to the environment. Storm drains and combined sewer overflows can cause load spikes during monsoon periods.

2. Urban runoff and mismanaged solid waste

Fragments of construction plastics, tire wear particles, road markings, synthetic fabrics from laundry, and littered packaging are released into rivers, lakes, and drains. Higher MP abundance is frequently predicted by proximity to cities, markets, and industrial zones, according to reviews of Indian freshwater systems.

3. Industrial sources and microbeads legacy

Even if the use of microbeads in cosmetics has decreased worldwide, industrial pellets (nurdles) and legacy stocks can still find their way into rivers through unintentional spills and inadequate containment. Pellet-like MPs are commonly detected in sediments and strandlines by coastal monitoring.

4. Atmospheric fallout

Airborne fibers and fragments settle on catchments and water surfaces before washing into bodies of water. In South Asian riverine research, air settling has been identified as a significant input pathway.

Implications for ecosystems and people

Microplastics can carry associated chemicals and microorganisms, change physical habitats (e.g., light penetration, sediment structure), and are consumed by fish and invertebrates, some of which are significant in Indian diets. Concerns regarding trophic transfer have been raised by coastal studies that have found MPs in economically significant fishes throughout portions of the Indian coastline (although risk magnitudes are still being studied). Drinking water is one exposure pathway that is being examined from a human perspective. Several bottled water brands have been found to have MPs in Indian studies; the particle concentrations vary depending on the brand and analytical technique. The existence of tiny particles, such as nanoplastics that are not detectable by conventional techniques, encourages preventative measures even if the health effects are still being determined.

Microplastics pose ecological, health, and sustainability challenges by contaminating ecosystems, harming biodiversity, threatening food safety, and disrupting biogeochemical cycles. Their persistence makes them a long-term environmental concern, requiring urgent global action in waste reduction, plastic alternatives, and pollution control. According to shapes of microplastics, the various environmental concern they can raise is summarised in a Table 1.

Policy and program landscape

Significant upstream measures have been taken by India: the Plastic Waste Management Rules, 2016 created duties for collection, processing, and segregation; the 2022 amendments introduced Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) for plastic packaging and outlawed a number of single-use plastic products across the country. State pollution control boards and the CPCB’s EPR portal are used to operationalize implementation.

Large-scale sanitation and river-rejuvenation initiatives (like Namami Gange) are boosting nature-based solutions and increasing sewage treatment capacity on the water side. By capturing solids and enhancing waste management throughout catchments, these initiatives can indirectly reduce MP loads. A baseline for coasts and nearshore waters is being established by government monitoring and reporting through NCCR.

Standards:

As techniques become more standardized and risk thresholds are improved, several researchers draw attention to the fact that microplastics are not currently included as a controlled parameter in IS 10500 drinking water requirements.

Methodological challenges

• Comparability of sampling: Variations in mesh sizes, volumes, and sample matrices (biota, sediments, and surface versus deep water) make cross-basin comparisons challenging.

• Identification limits: Spectroscopic confirmation (µ-FTIR/µ Raman) is the most accurate but requires a lot of resources; visual sorting can misclassify particles.

• Nanoplastics: Although particles smaller than 1 µm are hard to measure using standard techniques, they might constitute the most bioavailable portion, necessitating method development and inter-lab research.

What would make the biggest difference?

1. Reduce plastic leakage at source

Government needs to increase deposit-return schemes for beverage containers, enforce the Single Use Plastic (SUP) ban and Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) compliance more strictly, and provide incentives for high-quality recycling and reuse. Producers, brands, and municipalities can all be brought into alignment with clear guidelines and audits conducted under the CPCB’s EPR framework.

2. Upgrade wastewater and stormwater systems

To avoid re-release, optimize tertiary treatment, add advanced solids capture (such as disk filters or finer screens), and manage sludge. Install litter traps in urban drains and keep them maintained prior to the height of the monsoon season. Targeted upgrades can result in short-term reductions because evidence from Indian WWTPs indicates that present systems lower MPs but do not eliminate them.

3. Nature-based interception

While retaining a portion of microplastics (with consideration for wetland media management), constructed wetlands and riparian buer restoration within river programs can slow flows and settle particles, co-benefitting nutrient and pathogen control.

4. Monitoring that informs action

Expand national surveillance using harmonized methods across rivers, lakes, groundwater, and coastal nodes—building on NCCR’s coastal work—to map hotspots, track trends, and evaluate interventions. Connect environmental loads to possible exposures by incorporating biota and drinking-water endpoints.

5. Research priorities

• Fate and transport across monsoon hydrology and dam regulated reaches.

• Groundwater pathways in urban/peri-urban settings.

• Source apportionment (textiles vs. packaging vs. tires) to target measures effectively.

• Human health: bioaccessibility, mixtures with adsorbed contaminants, and risk-based thresholds for drinking water.